My parents spent their Thursdays chasing ghosts.

Every week, on my father’s day off, they’d drive to some distant library or cemetery, hunting for traces of people who’d been dead for a century or more. They’d return home exhausted, clutching photocopies and scribbled notes, excited about some census record or tombstone inscription.

I thought they were crazy.

I had zero interest in genealogy. None. I was busy living my life, raising my family, building my own story. Why would I care about people I’d never met?

Then, as these things go, time passed. My parents grew older. Their memories began to fade. And suddenly, I found myself wishing I’d paid attention during all those Thursday expeditions.

Starting Fresh (Sort Of)

When my mother passed, I inherited most of her genealogy books and records. She’d been meticulous—binders full of family group sheets, pedigree charts, and handwritten notes. But her computer had crashed years earlier, taking all her digital files with it. I gave the hard drive to the best computer person I knew, Steve Fuller, hoping for a miracle recovery, but those files were gone.

So I started fresh, using Mom’s paper records as my foundation and building from there.

I joined Ancestry.com and dove in headfirst. And I’ll confess something embarrassing: I fell into the copy-and-paste trap. You know what I mean if you’ve ever done genealogy online—you find someone else’s tree with your ancestor’s name, and suddenly you’re clicking “add to tree” without really verifying anything. It’s so easy. So tempting.

But as I learned more, I realized I’d been building a house on sand.

The Detective Work

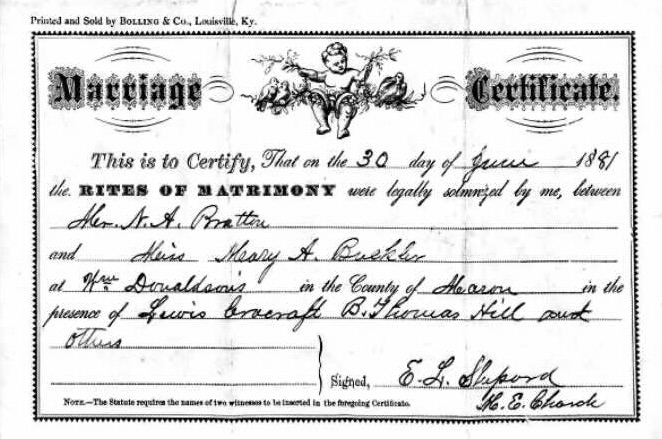

Now I’m going back through everything, reworking my tree with one goal: facts. Cold, hard facts backed by primary sources. Birth certificates. Census records. Marriage licenses. Obituaries. Military records.

If it’s a family story—and we all have those wonderful, probably-embellished tales passed down through generations—I’ll share it, but I’ll label it honestly: “According to family tradition…” or “The story goes that…”

That’s the part I love most now: the detective work. The research. The thrill of finding that one document that confirms something or, even better, solves a mystery that’s been nagging at me for months.

What surprised me most? The emotional connections.

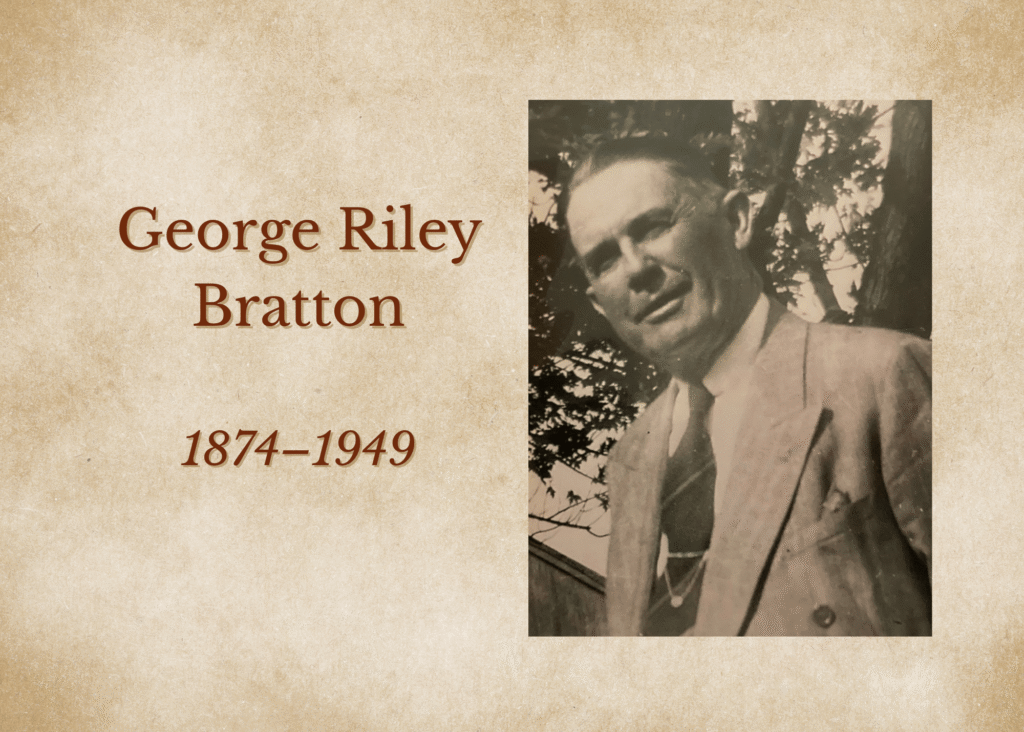

I never expected to feel anything for people I never met. But I do. I think about George Riley Bratton, my great-grandfather, and wonder what he thought about when he farmed that Kentucky land. I wonder about the women who kept households running without electricity or running water, who buried children, who endured hardships I can barely imagine.

They’re not just names and dates anymore. They’re people. My people.

Why I’m Telling Their Stories

A few years ago, I decided I wanted to write a book. I’d compile everything I’d learned about my ancestors into one comprehensive family history that future generations could treasure.

I made it about three chapters before I wanted to throw my computer out the window.

It was overwhelming. Some family lines are incredibly well-documented—I can trace them back centuries with solid evidence. Others hit brick walls in the 1800s with frustratingly little information. How do you write a coherent book when half your subjects are missing?

I gained a whole new respect for published genealogists.

So I pivoted. Instead of a book, I started a blog: Stories Gathered & Remembered. Every other week, I post about a different ancestor. Sometimes it’s someone I know well, with documents and photos and stories. Sometimes it’s someone more mysterious, where I share what little I know and acknowledge the gaps.

The blog format works for me. I can share one story at a time without the pressure of creating a perfect, comprehensive volume. And I’m accomplishing my real goal: making sure these people aren’t forgotten.

Tools, Tips, and Hard-Earned Lessons

Along the way, I’ve gathered some tools and lessons—some learned the easy way, some learned the hard way.

My Go-To Resources

I rely heavily on Ancestry.com. It’s a paid subscription, but worth every penny for me. Census records are readily available, and you can often find obituaries, marriage licenses, and birth records. I also use FamilySearch.org, which is FREE and has an excellent database of records. Between these two sites, I can usually find what I’m looking for—or at least get pointed in the right direction.

There are other sites available, but these are the two I rely on most. (And no, I’m not an affiliate of either—just a satisfied user.)

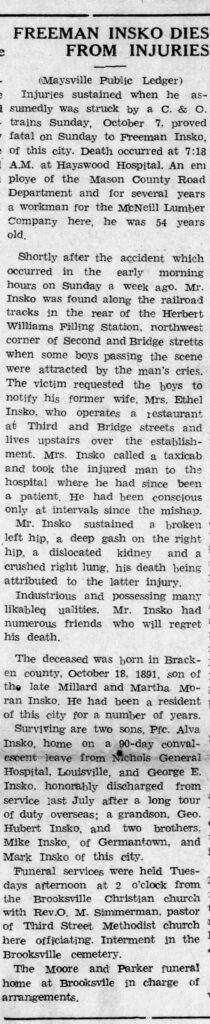

I also find newspapers.com helpful. Again, I pay for it, but there is nothing like a good obituary to gather facts. Obituaries often list spouses, children, parents, where someone was born, where they lived, their occupation, and sometimes even cause of death. They’re genealogy gold.

FindAGrave.com is a free resource where volunteers have photographed headstones in cemeteries across the country. Some entries include pretty good biographies—listing spouses, children, whether the person was a veteran of a war. It’s an invaluable tool, especially when you can’t travel to distant cemeteries yourself.

Most of my relatives are in Kentucky, and I’ve found that local historical societies are able to provide information you can’t find anywhere else. I’ve received obituaries and military records from local organizations and even from government sources (like Kentucky military records) for free—just for asking. I’m amazed at how promptly my requests are answered. The people who work in these places are passionate about their work, and they genuinely want to help.

The “Heritage We Wish We Had” Problem

Here’s something I’ve discovered: certain family stories really need to be looked at closely. People want to have Native American heritage. They want to be Mayflower descendants. They want to have a relative who fought in the Revolutionary War.

And people will really stretch the truth on these.

Please, if you decide to build your own family tree, do NOT just copy and paste from other people’s trees. Use your brain. This person died in 1837 but supposedly served for the Confederacy in the Civil War? Likely not. (The Civil War was fought from 1861-1865, in case you’re fuzzy on your history.)

I’ve read countless family trees claiming an ancestor fought in the Revolutionary War, but when I search for records? Nothing. If that’s your family story, share it—but be honest: “According to family tradition, John fought in the Revolutionary War, but no military records have been found to confirm this.”

When DNA Rewrites Everything

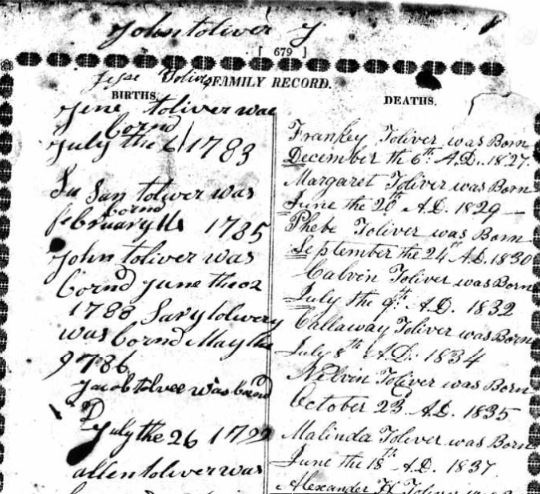

I found a glaring mistake on the Tolliver side of my family—one that completely upended what we’d believed for generations.

My father told me that our Tolliver ancestors were descended from the Taliaferros of Italy, and that the spelling of the name had simply changed over time. Our family believed this lineage:

Bartholomew Taliaferro, a subject of the Duke of Venice, was documented through probate records and his will dated May 12, 1617. He was a merchant and a member of the Band of Gentlemen Musicians to Queen Elizabeth. His son Francis lived as a gentleman farmer in England. Francis’s son Robert—known as “The Immigrant”—settled in York County, Virginia around 1647. Robert eventually moved to “Taliaferro’s Mount” on the Rappahannock River near present-day Port Royal. He was the founder of a significant and very wealthy Virginia family, one of the First Families of Virginia.

We could trace these three Taliaferros reliably through wills, church records, probate documents, and deeds from Italy to Colonial America.

But after Robert “The Immigrant” and his wife Sarah Katherine Debman, the lineage gets murky. They had at least six sons and four daughters. Their son Robert Taliaferro II married Sarah Catlett. Their son Robert Taliaferro III married Margaret French around 1710.

And then? The paper trail goes cold.

I couldn’t find evidence-based documentation for the continued lineage of this line of Taliaferros. I also couldn’t locate a transition from Taliaferro to Toliver. In fact, most records for the five Toliver brothers refer to them as “Tolivers” from the start. The records begin in North Carolina with no clear connection back to Virginia.

This wasn’t entirely surprising. Early American colonial records outside of New England were most often documented in family Bibles, many of which have been lost over time.

Enter DNA testing.

The Family Tree DNA website hosts the Toliver Family Project, where 152 male members of the Tolliver family have participated by sharing their Y-DNA (the chromosome that passes virtually unchanged from father to son, showing direct paternal ancestry).

The results? Not one family, but THREE.

The first group is the actual Taliaferro family—Italian in origin, merchants who came to Virginia in the 17th century and became wealthy landowners. This is the smallest group. This is the ancestry my father believed we belonged to.

We don’t.

The second group—the one that includes my father Henry L. Fuller, Jr.—traces to four of the Toliver brothers: William, Moses, Jesse, and Charles. This family has its roots in Western Europe. The haplogroup R-M269 is common throughout the United States, and the majority of Tolivers belong to this group.

The third group, descendants of the fifth brother John, doesn’t match the DNA of either the Taliaferro family or the other four brothers. This group is Mediterranean/Spanish in origin. Because traditional genealogical evidence like censuses and land records indicates there was a connection between John and the other brothers, it’s possible he was their cousin on the maternal side—or there could have been a break in the male line somewhere (adoption, step-child, or out-of-wedlock birth).

Bottom line: The Y-DNA testing proved there is NO relationship between the Taliaferro family and the Toliver families. The family story my father told me? Wrong.

It was humbling. And fascinating.

Navigating the Messy Reality of Records

As you dig into genealogy, you’ll encounter name spelling variations and families who named all their male children with the same given name (looking at you, families with six Johns). This is especially true with census records.

Remember: the census taker wrote down what he thought he heard. Really, the name is Buchanan, not Buck. And did you know that in some earlier census records, a neighbor could give the recorder your census information? Now the informant is recorded, but you’re still relying on someone else’s memory. Some communities were tight-knit. Some were not.

My Research Process

When I build a biography of an ancestor, I start with the facts I have. Where are my gaps? What do I know for certain, and what’s still missing?

Then I search specifically for those gaps—or I look to gather additional information that expands on the facts I already have. Once I’ve exhausted my research (or at least done a thorough job), I put it all together into a narrative.

And I always list my sources. Always. This allows someone else to go back and verify the information for themselves, or to build on what I’ve found.

One More Thing

Even if you aren’t interested in genealogy, do this one thing: ASK your family members about their lives. Hit record when Grandpa is telling his stories. Believe me, at some point in your life you’ll be glad you have that information.

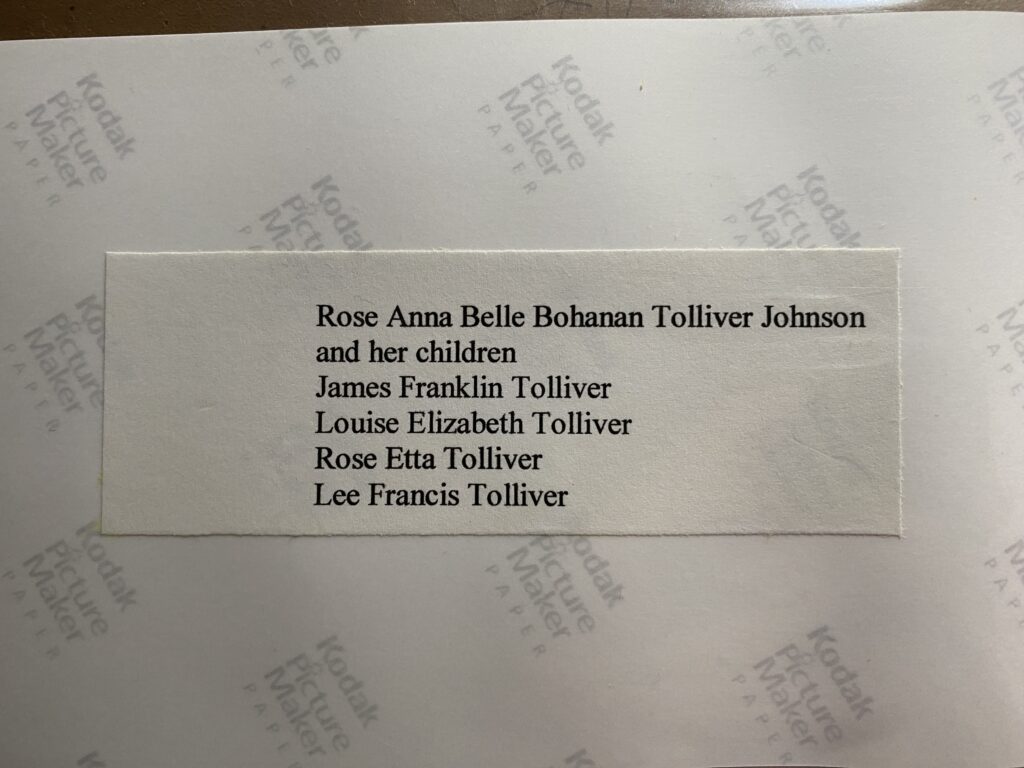

And LABEL YOUR PICTURES.

My mom has many photos with no labels. Sometimes I can figure out who someone is because I have another labeled picture where they look the same. Most of the time? I don’t have a clue. Those faces are lost to me now.

Don’t let that happen to your family.

Preserving What Matters

Many of my blog readers are family members—cousins I’ve connected with, descendants of common ancestors, people who care about the same names I do. We’re all working together, in a way, to ensure that the legacy of our ancestors lives on.

Because here’s what I’ve learned: if we don’t tell their stories, those stories disappear. The memories fade. The documents get thrown away. The photos end up in antique store boxes marked “unknown family.”

My parents understood that. That’s why they spent those Thursdays driving to libraries and cemeteries when they could have been relaxing at home.

I finally get it now.

I just wish I’d understood it sooner, when I could have gone with them on those Thursday adventures and asked all the questions I have now.

But that’s why I do this work today—so the next generation won’t have the same regrets.